I flash through the local newspapers too fast and not fast enough. I have become both an eccentric source of discombobulated, de-contextualized local history, and a bore. I simply can’t parse time that quickly, but I can’t help but try. I can pick any moment to puddle jump, but I can’t stay there, and even though the papers speak to me in an ever-present tense, I can only relate in the past tense.

When I arrive to the 1981 box of Homer News, I feel a sense revelry: certainly there will be a shift the year I was born!! My timeline is about to begin! I lookout for birth announcements of childhood friends and cross my fingers that in the chaos of running a 24-hour taxi cab company, that my parents will remember to put mine in the paper. On some level, I have a childlike understanding of time: it doesn’t feel like the world existed until I have my own consciousness. But of course the world existed, and is running just fine without me in it in early 1981.

A story in January 1981 catches my attention: a rancher on the North Fork reports that a wolf pack killed two of his calves, one horse, and one dog. A reporter interviews Alaska Fish and Game biologist Ted Spraker, who acknowledges “that wolves may have been involved in the killings, which he [Spraker] sees as beyond the capabilities of coyotes.” I love the imprecision of the story. The room for imagination. The biologist, not wanting to create panic, insists that this kind of killing is uncommon for the area. People shouldn’t be scared.

And just like that— my parents’ memories surface in me as if they are my own memories.

My parents lived on the North Fork, a dirt road curving from the main highway, long enough to be impacted by the experience, though I can’t say how long that was: one winter or five winters, doesn’t matter as much as that it became a part of our lore. They used Folgers coffee cans when it was too cold to walk to the outhouse. Going to town meant sliding down Thrill Hill in a janky trunk with brakes as an afterthought. They likely had to haul water and it’s unlikely they had a telephone.

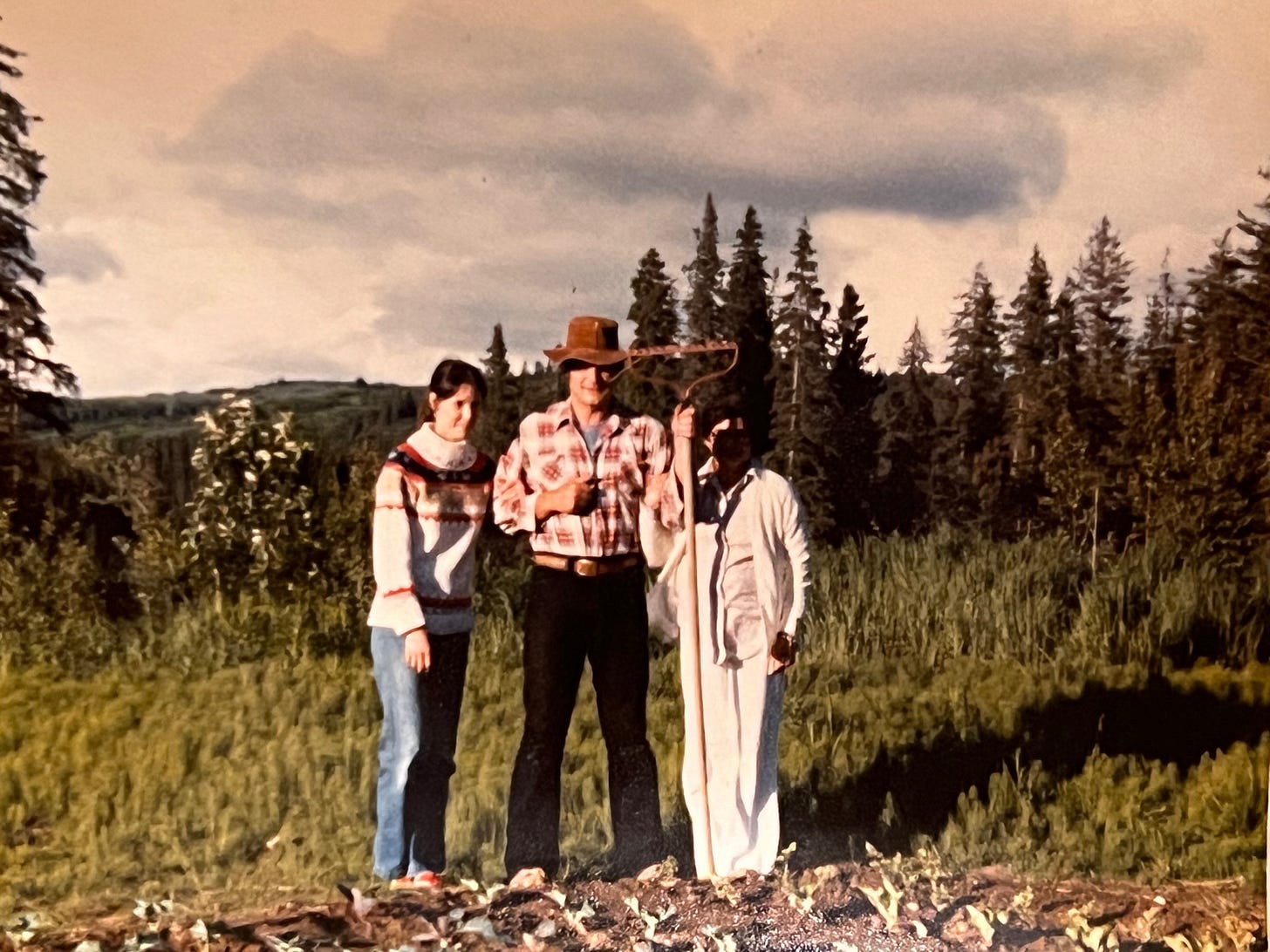

In an old photo recovered from a heap in my garage, my dad, not yet 30, wears a plaid shirt and brandishes a rake that shadow’s his mother’s face. He’s showing off his off-grid life on the North Fork to his mom, who is visiting from Pennsylvania. She is dressed in all-white, probably still wishing her son had become a doctor. My beautiful dark-haired mother completes the picture, in jeans and a sweater and an inscrutable not-quite-smile. I suspect she feels a mixture of wanting to please her mother-in-law and uncertainty of life on a dirt road in the middle of nowhere.

Maybe the biologist was right and there wasn’t need to panic. But those winters were especially cold, and everyone was lean and hungry, especially the wolves. At least, that’s how my dad would begin when I would beg him to tell me a bedtime story, “I want something scary Dad!” It doesn’t matter that I’m 11 years old and know all the stories he’s willing to tell a kid, each time he renders them differently. Each story has a life of its own.

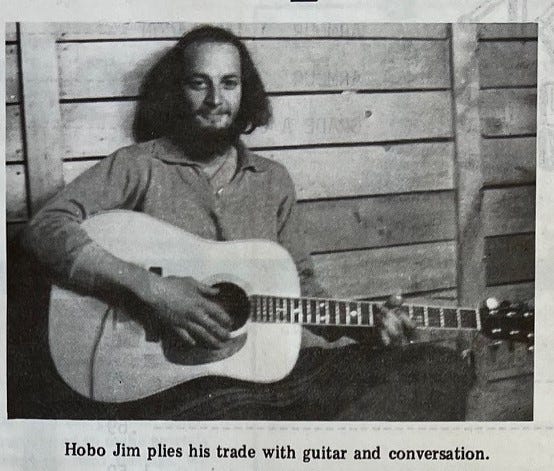

In those days one of his closest friends was Hobo Jim, a balladeer in the making also living on the North Fork. They’re up past midnight crafting a song together, though I can’t tell you which one. After midnight, my father feels a psychic pressure from my mom to get home. She isn’t pregnant with me yet, but I’m nearby waiting in the cosmic margins of time. She’s tolerating this lifestyle for a man she loves, but loneliness frays her patience. There’s likely hell to pay for being out so late.

Or at least that is what this 40-something year old me tags on to the memory.

It’s well below zero degrees. My dad shoves his hands in his pockets and watches the steam from his breath rise as he walks the snow trail from the cabin to his truck. It’s a long enough stretch to remind a person of their insignificance. The snow reflects the starry night and everything twinkles. His jacket smells like wood smoke and he feels satisfaction: this cold harsh life is his.

The wolves feel the heat emanating from the cabin. They notice the door open; watch a man descend down the front porch steps. By the time my father recognizes the danger, he is too far down the trail to his truck to turn around. He is frozen. Afraid to walk in any direction. Surrounded.

“But Dad! How did you know they were there? Could you hear them?”

“I don’t know how to tell you. I just knew. I could feel them all around me. “

“But Dad! I wasn’t even born yet!”

“I know. I stopped and stood very still. I didn’t have anywhere I could go. Then, I let out a blood-curling ‘Hobooooo!’ and he came out on the porch and fired his rifle and I could hear all of the wolves run.”

And then the re-constructed memory distorts, I can’t see if he finishes the walk to the truck or goes back to the cabin. But I can hear one more whisp:

“It could have all been over, right then,” my dad says, his blue ball cap askew on his thinning hair and his brown eyes sparking with the memory. We are quiet, as the thrill of the story settles in. I shift my attention to the stars outside my bedroom window; the night is clear and snow glitters next to the wood shed. A log pops in our Franklin woodstove, and my hair is still damp from an evening shower. My plaid blanket scratches my chin, but I feel safe surrounded by the log walls of my bedroom. The world is wild, but my place in it is secure. Still, it’s doubtful that I will sleep after this begged-for bedtime story.

This project began as building an archive of my father’s letters to the editor. But in these early years of making a life in Alaska, his letters are rare like agates. Instead I find something else, something close to memory—but not my memory. I see my parents in the subtext of stories that don’t have anything to do with them, but share a common geography and moment in time. I see myself in places I wasn’t alive to be present for. By which I mean: I remember the starry night. I remember how black it was. How grateful I was for the starlight to guide my father’s footsteps. And when I step outside on a clear night in winter, I am still afraid that the wolves might hunt me.

Until Next Time,

Mercedes

Notes:

1.)I am humbled by the many eyes on this series and by the encouragement readers have offered. I was surprised when people began pledging support of this project, which is a labor of love and creativity. Thank you. Financial support will go toward building an interactive website to house my dad’s letters, project gems, and my essays.

2.) Story-making is a collaborative endeavor. While most of these essays are crafted alone at 5 am with a cup of coffee on my couch, the project map was generated in the brilliant Janelle Hardy’s Art of Personal Mythmaking 5-month course. This is more than a typical creative writing workshop, it’s an opportunity to re-envision your relationship with your life story. The class is offered in self-directed or live options, the next begins in January 2024.

3.) Did you know I debuted in the paper before my dad? After a year of snooping about the stacks, I discovered the birth announcements of my oldest, dearest friend, Carolyn Norton and I were separated by a single issue of the Homer News!

4.) Next essay: A holiday theme, with a roast that catches fire, a Christmas tree that flowers, and, again, the stars on a clear cold night.

5.) New to this series? Check out the first and second essays that ground the project.

You do have a golden scribe 🖋️ nestled in your hand and heart!

Your stories are very fun and interesting to read. I especially liked the photo too. Your Dad was a special guy and I'm sure your Mom was too. It is so good to read these, so thanks for embarking on this project.