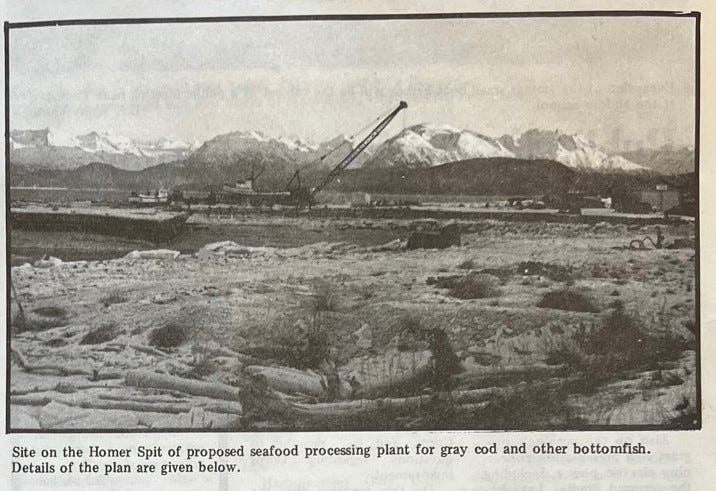

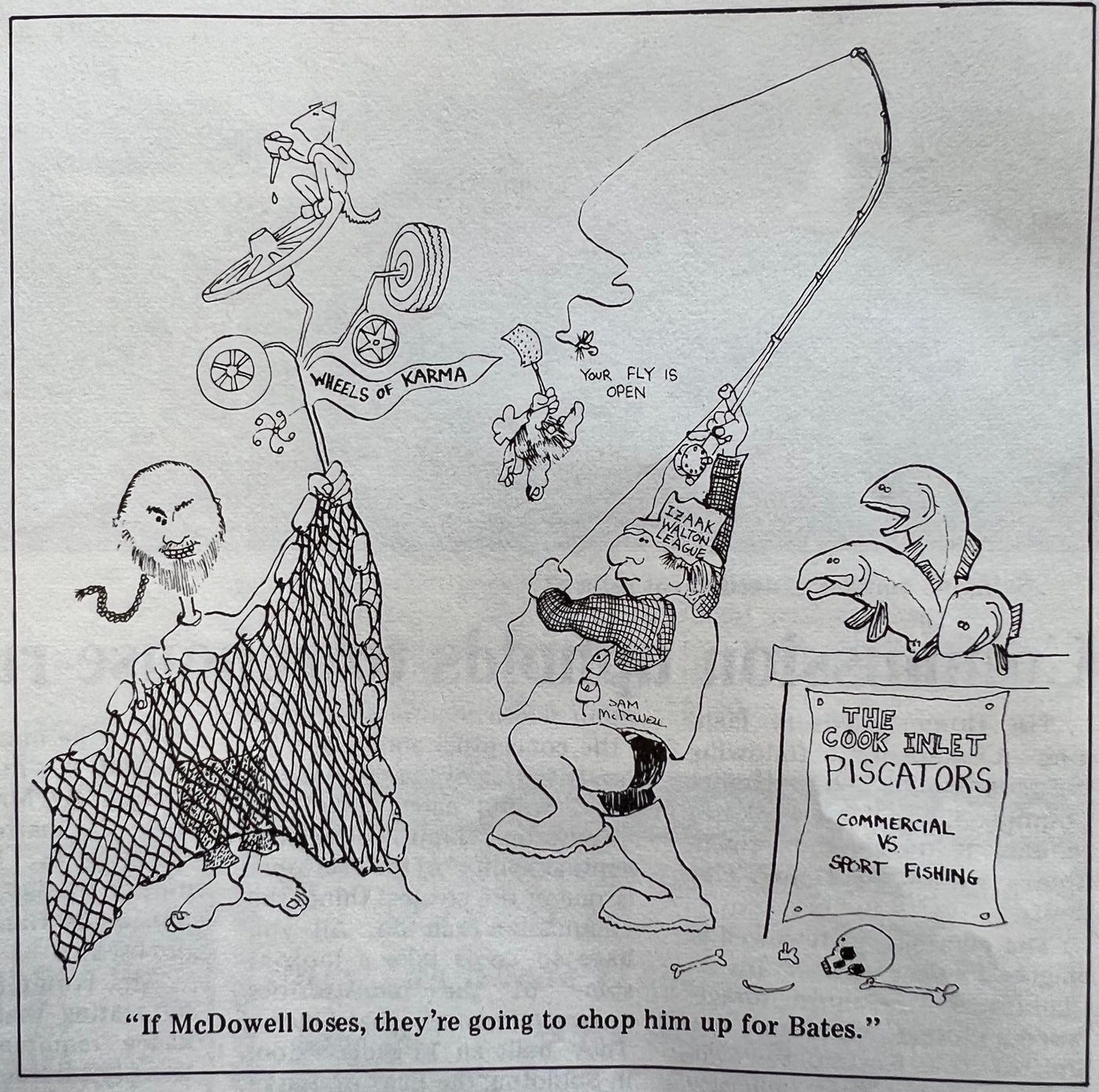

January 1978 was unseasonably warm and icy. Mail was slow from Anchorage. A second bank was about to open in Homer. The future of the Bradley Lake dam, which would become an important supply of electricity for the community, was still uncertain, and Brother Asaiah Bates was effectively and poetically roasting Sam McDowell, who was hell-bent on privileging sports fishing over commercial fishing.

If you’re not from around here, it might be hard to appreciate the seismic activity of that paragraph. Let me just say: the groundwork for the future from which I write, was well underway.

Also of interest that month: the Fireman’s Ball on January 28, some good deals at Proctors Grocery, signs of Bigfoot in Iliamna, a hold-up at the Grog Shop liquor store, and the robber who got away on foot. Margaret Schools was about to have a baby, but she feared the roads were too icy to make it to the hospital.

I wasn’t yet born, but these are the details that I hold from reading the January 1978 issues of the Homer News, grayed with time and spread out over the table in the library study room. The familiar names and faces make me grin with recognition: everyone was so young.

On my dad’s 70th birthday, I began a project to archive the letters he wrote to the local newspaper from sometime in the 1980s to 2016, when he died. In addition to his letters, I collect digital newspaper clippings of moments, ideas, and events that in some way strike me. In the process, I’m uncovering community conversations and concerns that continue to reverberate and, in many cases, never lost their ability to quicken the pulse of residents. People here care about the economics and necessities of a small town, and what it means to make a life in this far-flung corner of the world.

I’m curious where my parents might exist in the inky smudges of time. Family lore is that they were nearly arrested as runaways when they got off the ferry from Kodiak Island, my mother driving the decision to relocate to a place a little less wild and possibly more hospitable. They got what they could afford: a tiny cabin on the North Fork with a potbelly wood stove and a ration of flour and mayonnaise to make biscuits.

I actually don’t know if there was a potbelly wood stove.

“Life’s an approximation, we do our best,” was one of my dad’s favorite sayings, so I will do my best, on occasion employing my dad’s skill of embellishment to give the stories texture and context—hopefully crafting something worth reading.

Anyway, in 1978 I’m three years out from conception. Still, I can imagine the newspaper laid out on my parent’s kitchen table, an ashtray resting nearby, and a few drops of black coffee spilled on the corners. Smoke swirls in the air, but neither of them notices it. My dad, in a blue plaid flannel, is hunched over reading. Mom tries to talk to him, but he can’t hear her because he’s deep in thought. I wasn’t there. But I swear I can smell the cigarette smoke mixed with the wood stove. I can hear the chair scraping the floor as my dad, still distracted, gets up to pour another cup of coffee.

My father, a night dispatcher for the electric company, wrote letters to the editor as a way to engage in the democratic process by sparking conversation. In reality, he mostly rallied fellow liberals, giving them validation and historical reference for their opinions. I’m guilty of not reading enough of his letters while he was alive. I didn’t have to—I took my dad’s presence and opinions for granted. But now, I miss knowing how he would have made sense of the past decade.

I’m interested in incremental movement. In the same way our town has grown a day at a time, with present-day infrastructure still a dream in 1978, what did my dad create by penning one letter at a time? Did he grow as a human? Did he shift conversations or directions? Did the town change him? Did he change the town? What does it mean to be vocal about national events in far-flung America— is it possible to have an impact?

Of concern is the possibility that I misinterpret a particular narrative. What if I should get “it” wrong? I have faith that local readers will help build the story by sharing their recollections—and letting me know when I go astray.

I’m relying on the goodness of imagination, the imprecision of memories, old family pictures, conversations with friends and family, and the essence of the times gleaned from the pages of the Homer News to craft a narrative from there to here and then and now, with plenty of winding side roads and ideas.

Stay tuned,

Mercedes

Notes:

Thanks for reading. If you are receiving this inaugural email, it is because you were either on an older email list of mine or because we’ve had a conversation about this project or because I think it may interest you. I hope to send 2-3 newsletters a month. You can unsubscribe at any time. But you’re also welcome to share. You may leave comments or email me directly at mercedesoleary@gmail.com.

Margaret Schools, where are you? You slipped January 1978 where my memory places you, and I suspect landed in January 1979 or 1980. Memory is unreliable in part because the rhythms and seasons of our complaints are so steady.

And just for fun, old-timers might appreciate this:

I love this quote, ““Life’s an approximation, we do our best.”

"..it might be hard to appreciate the seismic activity of that paragraph." Congratulations of quaking new ground, here, Mercedes! Can't wait to read and read more.