I am back in my home state of Alaska, where the fervency of green and endless summer light is creating a minor solstice mania. My rhubarb grew five feet in my absence, and it took three days to mow the deep, thick lawn. I go to bed too late and wake up too early. Everything seems possible and remains half-finished. The suitcases are still not unpacked, but I weeded the perennials! My daughter begged to do a lemonade stand and kids came over to play and there was a sweet gangly baby moose at the bottom of the yard. As it turns out, these things matter more than to-do lists.

I’ve barely been home a week and my dopamine feels out of control. I’m on a kind of “things are okay for now” high, and, as I told my aunt, “okay” has never felt better.

Meanwhile, back in the newspaper stacks at the library, there are more than 50 years of solstices to celebrate.

But of course, I have a favorite.

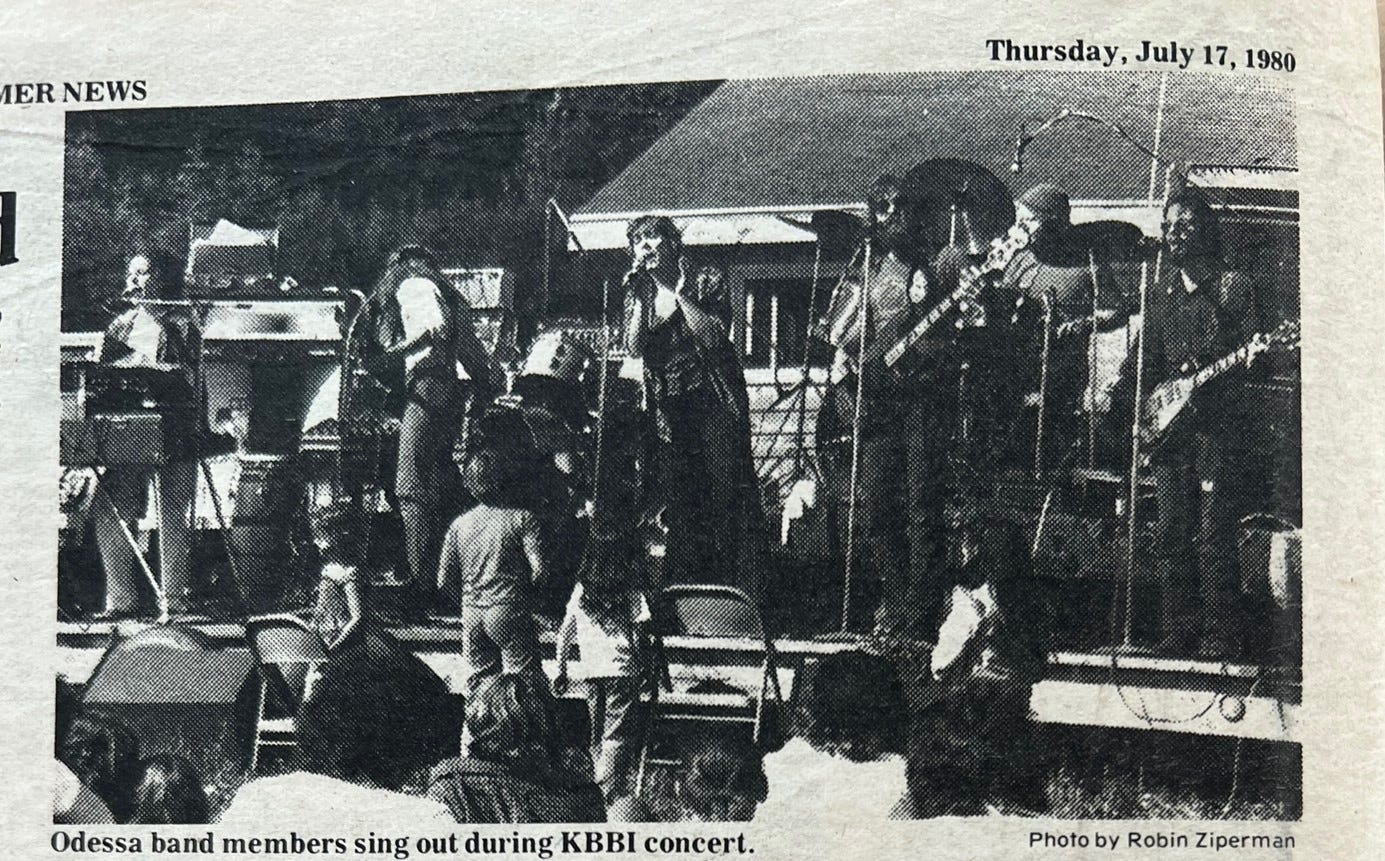

I imagine the summer of 1980 as green as the alder palace and pushki field outside of my bedroom window, and as dusty as my long dirt driveway. Pictures in the newspaper look a little hazy, as if the dust never settled all summer. The pixelated black and white photos try to capture the glitter of the bay, and I know the energy derived from the ceaseless sun was just as intoxicating as it is now.

That summer, my parents must have been crisscrossing Pioneer Avenue and taking turns driving taxi cab passengers to the Spit. There was always someone by the landline and the CB radio to dispatch a ride somewhere. I don’t know if my parents were married, but I do know that they were the proud, exhausted, relatively new owners of Inlet Taxi. I also surmise some of my dad’s brothers and sisters were hanging around to help their older brother’s enterprise.

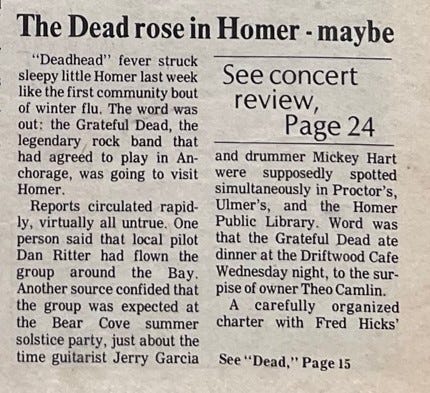

The June 26, 1980 headline “The Dead rose in Homer-maybe” catches my attention. The article reads a little like a tabloid: “ ‘Deadhead’ fever struck sleepy little Homer last week like the first bout of winter flu,” then goes on to describe the “surprise” visit by rock stars: “Reports circulated rapidly, virtually all untrue….the group was expected at the Bear Cove summer solstice party, just about the time guitarist Jerry Garcia and drummer Micky Hart were supposedly spotted simultaneously in Proctor’s, Ulmer’s, and the Homer Public Library.”

And just like that, I hear the sound of my dad’s laugh. I see him shaking his head, and a family legend is exposed.

The Grateful Dead definitely came to Homer.

And it’s not much of a leap to think they enjoyed the solstice frenzy and summer parties.

But first, the band needed a pick-up from the airport—and who do you think they called? Inlet Taxi, and my parents swore they would keep the famous band’s visit a secret.

At the time the airport was only a runway with a few outbuildings. Homer wasn’t fancy, but it was a great place to escape fame for a few days. The taxis weren’t fancy either: why bother washing something that will only be covered in dust 10 minutes later? I don’t know how many vehicles were in the cab fleet, or if “fleet” is too grand of a word for a few cars and vans cobbled together.

When my dad told the story, he never got much farther than the airport. After the bands’ luggage was loaded, Jerry himself settled into the van—only to immediately fall through the rusted-out floor. The passengers weren’t fussy, but no one expected a Flintstone mobile either. The band had attempted to secure their privacy, but they hadn’t thought to assess the safety of the only cab option in Homer. It was at this point in the telling of the event that my dad could barely contain himself: the paradox of the celebrity band and the janky vehicle always left him in a fit of laughter, barely able to talk.

But because of my dad’s bent toward embellishment, I don’t trust his version entirely—I don’t quite believe it was Jerry, but I know his presence makes the story better. Maybe it wasn’t even my dad driving. My dad’s rendition is a comedy sketch, an anecdote that became family legend, a borrowed memory.

It likely took several cabs to ferry the band members and roadies to their destinations—places any traveler needs to go to resupply. So of course there were simultaneous sightings, how could there not be? CB radios, which were not uncommon to own in those days, were about as private as a grocery store conversation. So several people may have tuned in to hear where the famous band was being driven, or perhaps, the cabbies enjoyed keeping the band’s cover by spreading false rumors of their whereabouts.

The old newspapers smell slightly sweet, and the pages sometimes want to tear if they’re turned too quickly. If I close off my periphery vision, if I am only with the newspaper, it could be any decade. The flora and fauna are still following the same rhythms, the bay still glitters, and the promise of green has never broken. The town itself is both exactly the same and radically different. How is that possible? Is this what it feels like for time to collapse? I swear I could call Inlet Taxi and ask for a ride home.

When I first tried writing this essay (a year ago!), it was all about missing my parents and finding them in the subtext of the print. But now my focus has shifted to ensuring I am outlived by the generation I’m helping raise. Besides, there’s a subtle diffusion of my parents in everything. Love and grief are like that: the dead rise in us again and again.

This week there were no CB radios announcing our return, but going to the grocery store felt pretty darn close. I was stopped in the produce section by a mom from the school PTO happy to see we were back, and then as I was getting buckled up, my midwife from a decade ago parked her grocery cart and walked over just to set eyes on the baby she once monitored and measured. I rolled down the window so she could see my kiddo, looking like any kid who spent the day playing outside. “Things are on the upswing,” I said, adding, “fingers crossed they stay that way.”

The next day I went to get my hair done by the same beautiful red-haired man who has cut and dyed my hair off and on for nearly 20 years. I was remiss for not hugging him. While he colored and trimmed, we traded travails and raged for each other—and everything felt a little better afterward.

The thing about being in a small town is that all of our stories are muddled together. Decades pass indifferently, and we are all still driving the same pot-holed roads together. It’s easy to talk about a small town with derision, but it’s hard to get away with anything around here, good or bad. I find some comfort in that. I’m not suggesting things are perfect here, there is so much work to be done everywhere I look. But there is a wildness still coursing through this place that so far seems to defy time, is fueled by the sun and moon, and is teeming with humanity.

The real joke is the idea that Grateful Dead’s visit to Homer could be kept secret when everyone was in on keeping the secret.

Until next time,

Mercedes

Notes:

1.)Grateful Dead was scheduled to play in Anchorage on June 19, 20, and 21, so perhaps they came down the following day… or maybe it was only part of the band? The specifics are still unspecific. Still makes for a fun story! But if you have details to add, please feel free to share them!

2.)Thanks for reading! If you’re new to this project, this piece will ground you, or if you missed last month’s dispatch you can find it here.

3.) If you’re from around here, what stories from the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s do you think are worth re-telling? I have some ideas, and the pile of letters by my dad and others is accumulating! Email me if you have ideas to add to the pile.

Welcome home. Great read. I saw The Dead in Vermont when I was 15. I love the imagery of Jerry in the van with a big hole in it!

Lovely writing Mercedes, and I get a glimpse of who your Dad was in your telling. This moment in particular struck me: "there’s a subtle diffusion of my parents in everything. Love and grief are like that: the dead rise in us again and again." Yes.