Chronic illness and the wolf

Back in November, I was writing about wolves that surrounded my dad on the North Fork. At the time, I had my own wolf at my doorstep but I thought I could keep her satisfied on the porch. I wanted to believe that if I didn’t acknowledge the wolf and tended to my daughter (9), who was nearly constantly sick, the wolf would go away in the night.

Many of you, dear readers, know that winter 2024 was difficult for my family. Doctors told us that things weren’t so bad; kids get sick a lot. But then my daughter couldn't walk. We resisted taking her to the hospital until her immobility spread to her shoulders and I spoon-fed her on the couch.

By that time, she had already had extensive testing, and we suspected she had something that couldn’t be measured by typical means. Stories abound of post-viral conditions and the often accompanying post-exertional malaise (PEM), which can render even children bedbound for months and years. We were scared that the energy she would need to go to the hospital would push her too far.

Still, we were more scared we might have missed something. She was hospitalized for a week. She left still not able to walk, but no one knew why.

The wolf was devouring our daughter. But no one could see the wolf.

So, I pivoted. I stopped writing anything creative. I wrote letters to faraway hospitals and doctors. I made timelines that I asked my dad’s family to help edit. I researched NIH (National Institute of Health) studies and made friends with a mom going through a parallel struggle with her child. I politely argued with doctors. I pushed back when they suggested my 9-year-old had conversion disorder, a diagnosis that suggests “it’s all in her head.” Her dad and I advocated for treatments, well researched in places like Stanford, that hadn’t been used in our small town on a child.

And when she was well enough, I flew her to one of the top medical facilities in the country to run more diagnostics. I appreciated the efficiency with which we were able to access testing and doctors, even as I was distrustful of the treatments they suggested which were out of sync with the academic studies we were reading. My health insurance card, new to our family for a handful of months, felt like a golden ticket. So I kept reaching out to experts. I left a tearful message on a specialist’s voicemail: “My daughter can’t walk, and no one knows how to help us,” I struggled to get out. She took us on. She is one of the foremost experts on chronic illness in the country and she can see the wolf.

COVID-19 invited my daughter’s chronic illness, and an underlying constitution probably permitted the two-year slow disintegration to the hospital. Post-viral syndrome, long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) are all sister diagnoses, and they share friends with autonomic nervous system dysfunction. This kind of chronic illness impacts multi-systems and reveals itself uniquely in each individual, making it challenging to diagnose, and too often its complexity lends itself to medical practitioners dismissing it altogether.

No such thing as an end-stop

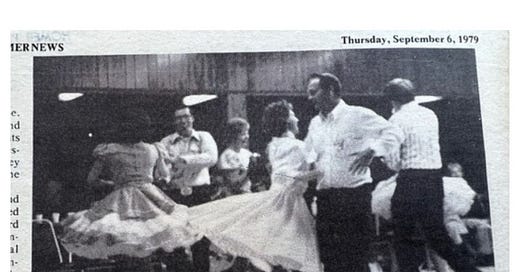

The spinning dancers at the top of this page? Her skirt caught in a spin, forever swirled behind her. Joy captured. Remembered. Even when I couldn’t write for this project, I thought about images like this from the Homer News. I thought about time stacked in the weekly papers across decades and how it all just keeps coming, the good, the bad, and somehow we survive it. Or we don’t. But others do.

Shortly before my daughter’s health went sideways, I sat next to a woman at a community event. I had just read a story in the Homer News that described what was probably one of the great tragedies of her life. The story was at least 30 years old. I wanted to say “I’m so sorry that happened,” but I didn’t. Even though her story was displayed in the public space of the local newspaper, to bring it up after so many decades felt like I was violating her private space. She was laughing and animated, absorbed in the present.

I thought of the woman as I tried to sleep next to my daughter in the hospital bed. My face was wet, but I couldn’t remember starting to cry. My daughter stirred and asked me to roll her over, because she couldn’t move on her own. I wanted to trade bodies with my 9-year-old; I wanted to be the one whose body was in so much pain.

After my daughter was settled, I thought more about the woman. She had survived something awful happening to her family, and she was still a vital participant in the community. She had made a beautiful life full of meaning; somehow we would too.

To say that “life keeps moving on” is trite and true—and an insidious reality for people with chronic illness who are aware of time passing around them, as they remain bedbound or housebound for months or years. In the darkest of days, I thought of images from the Homer News and their accompanying narratives: planes crashing, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, lives lost at sea, beloved businesses that shuttered, car accidents— moments that felt like an end-stop.

That night in the hospital when my daughter couldn’t move her body, felt like an end-stop.

Still…the tomorrows kept coming.

Hawaii

Today, I am writing this dispatch from the Big Island in Hawaii. My connection to the island is from my dad, who dreamed of running an organic farm here. He left me a plot of land and his best friend, both of whom need checking on occasionally. Also, it turns out, his dream left me an escape hatch.

In mid-April, I made a gamble that things would be okay and I rented a small house for the first month of summer. My daughter was improving, and it seemed like warm weather made a positive difference. Additionally, our home had become full of the rhythms and feelings left over from a long illness. Going to Hawaii on my dad’s borrowed dream (minus the organic farm), felt like a safe way to reset, rebuild our strength and stamina, and start creating different memories that didn’t revolve around sickness.

The day before we left, I sat in the library study room. Would I write an apology, a discontinuation of the project? Or would I keep going? It felt gratuitous even to have the space in mind to think of something besides my daughter’s health. I also felt guilty for my long absence. The first box I opened held the ending to a story I had been waiting for—the closing of Proctor’s Grocery. Then I found a letter from my dad and remembered that harvesting his words was what started this project.

I still want those damn letters.

Besides, if sifting through old newspapers has taught me anything it is that there is something elemental that holds us all together—the community that stitches us together. The difficulty of this past winter was made better by people reaching out and checking in, sending an email about their experiences, or a text that my family was in their thoughts. A terrible time was made better because I felt family and friends and even perfect strangers rooting for us.

For now, the wolf’s presence has diminished, and we’re working hard to keep it that way. There are flickers that remind us that we need to be careful, but for the past month, my daughter has been able to physically do whatever she’s wanted. We won’t know if this positive turn is permanent or temporary until we look back over months and years. In the meantime, I can’t unsee the disruption and pain long COVID, ME/CFS, and other chronic illnesses cause individuals and families near and far. It is real and not to be minimized.

I close with a picture of a girl and her dog on the beach. Because one image holds so much good. So much hope. A dog wagging her tail on the beach. A girl immersed in play. The beach. The caption describes the moment as “An irresistible force meets an immovable object.” Sounds like an apt summary of our winter: an insidious force took control of my daughter’s health, but we were immovable in our insistence to protect her.

And in the wake of that terrifying time, there is joy. I hope you have such deeply good moments this summer too.

I’ll be around. Writing again. The stories and updates may come more slowly than twice a month, but they’ll show up in your inbox again. There are a couple of fun stories coming up about summer solstice in 1980 and the time my dad adopted a pseudonym and annoyed a lot of women in town. I can’t decide whether the letter he wrote is funny or exasperating, so I’ll let you decide.

I’m back.

-Mercedes

Notes:

1.) It’s been a while! If you forget what this project is about, or if this is your first time stumbling on an essay by me, this piece will help orient you.

2.) Thanks for your patience and support. I thought I was living in one reality, and then life abruptly and radically shifted. I loathe not meeting expectations. I apologize for my long absence. If you need to unsubscribe, no hard feelings. I understand!

Mercedes, please let Blake and I know if we can help in any way. It's warm and dry here in the desert and we have a guest room. Just sayin'.

Oh what a lovely image of you, my dad, and your dogs serendipitously converging on the beach! I appreciate your support and well-wishes. Thank you.